Beloved Community

January 05, 2020 | Sarah Stewart

Passage: Ruth 1:16-18

Beloved Community

A sermon preached by the Rev. Sarah C. Stewart

First Unitarian Church (Second Parish in Worcester

Sunday, January 5, 2020

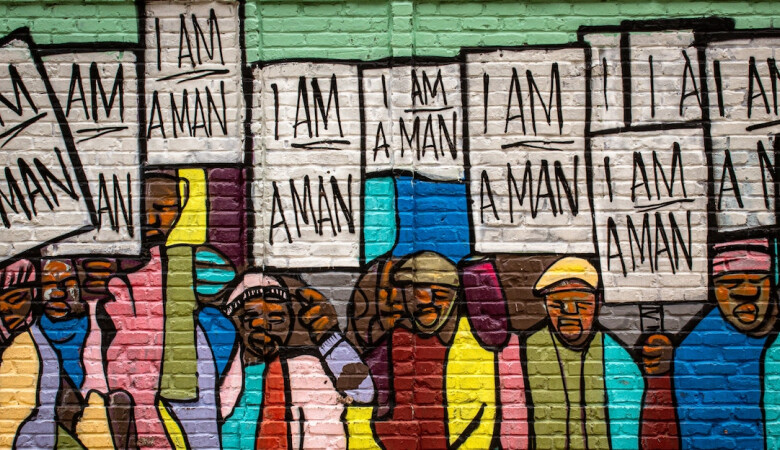

Beloved Community is the ideal and goal of how we live our lives together. This is the time of year when we hear the phrase “Beloved Community” more, as we prepare to remember the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday and celebrate Black History Month. King talked about the Beloved Community, a term he borrowed from a theologian of the prior generation, Josiah Royce. But what does Beloved Community mean?

Especially in church life, Beloved Community gets used to mean…all sorts of things. The kind of church we hope to be. The kind of church we believe we already are. The perfect human community in the hazy future toward which we’re walking. Or—if you look it up in the topic index in the back of the gray hymnal—it’s a shorthand for racial justice. The way we tend to use the phrase, Beloved Community seems very dreamy, very hopeful, not very practical or real. Not something we’re actually living in with the Spirit.

King believed that Beloved Community was the outcome which remained possible if human beings committed themselves to nonviolence in the pursuit of justice. King was a Christian minister and a supremely educated man, so he had read the writings of the theologian Josiah Royce. Royce, writing at the turn of the 20th century, coined the phrase Beloved Community. For Royce, and for King, the Beloved Community was human community infused with the Spirit, communities of loyalty, communities where people could come back into the fold despite inevitable mistakes.

Which makes me think of Ruth and Naomi from today’s reading.

The whole book of Ruth is four chapters long. It tells a story. It's hard to get that whole story into one reading. The part we heard today is the part that you most often hear—sometimes it's read at weddings. Although Ruth and Naomi were not a romantic couple. They were daughter-in-law and mother-in-law.

Naomi and her husband Elimelech were Jewish, from Judea. Famine forced them to leave their home and settle in a foreign country, Moab. There they had two sons, and those two sons married Moabite wives. One of those daughters-in-law was Ruth.

But then tragically all of the men died. First Elimelech, and then the two sons lost their lives. Alone and grieving, Naomi is ready to return to Judea to be with her people.

Now Ruth could have stayed where she was, she could have stayed with her people. She's still young, and very marriageable. She could have continued to have a life there. She doesn't have any loyalty in law, to this woman Naomi. She doesn't have to stay with her.

But she says to her mother-in-law no, I want to stay with you. I will become of your people. Your people will be my people. You're God will be be my God, and where you die, there I will be buried.

Ruth and Naomi, committing themselves to this loyalty tomorrow. one another, to yoking their lives together even though it's a world that doesn't value women's lives all that much. In fact, the rest of the story is kind of a mellow drama about how they work together to get a new husband for Ruth.

Ruth and Naomi can be our guides into Beloved Community. According to Royce, Beloved Community involves a shared past. Ruth and Naomi have a shared past. They have been part of the same family and loved the same people. They have mourned losses together.

Beloved Community involves a shared, hoped-for future. Ruth agrees to stay with Naomi, and says, “your people shall be my people, and your God my God. All our futures will be tied together.”

The last thing Royce said is that Beloved Communities share loyalty to some set of ideas. Ruth doesn’t just agree to stay and be Naomi’s family; she agrees to become Jewish and share the Jewish people’s ideals. She agrees to take on their way of life and become loyal to the things Naomi is already loyal to.

And then Martin Luther King added one thing to this. He said that Beloved Community is people who are holding open the possibility of being in community together even when the world has set them against each other.

The Israelites and their neighbors were often at war during this early time, and here we have a family that has made peace in the realm of those ethnic wars and has decided to be a family together. They have decided to stay together even when it would have been easy for them to think of each other as enemies or to not have their marriages to begin with. They are committed to that being in community together and remaining open to

Ruth and Naomi were trying to create Beloved Community in their family. They shared history, vision, values and they didn’t let their differences get in the way. Together, they withstood challenges and forged a future. The story doesn’t tell us about wrongdoing or reconciliation, but it is this kind of community that can withstand inevitable mistakes and bring people back into the fold.

If this were a Spirit Play story, we would ask: Where are you in this story? How can you help create Beloved Community in our personal lives, our church, and our society? To keep Beloved Community real, we need to think about how we can work to create this kind of community in our personal lives, in our church, and in our society.

Ruth and Naomi create Beloved Community in their family. Our families and friends are our most intimate communities.

Both Josiah Royce and Martin Luther King knew that we're not individuals on our own. No one was just formed the way they are, all by themselves unrelated to anybody else. No man is an island.

We are formed by the communities we are in. We are individuals only in community, and that presents its challenges. If we refuse to relate to the communities we're in and try to be too much on our own, we become untethered from what it means to be human. But on the other hand, the communities we're in can try to insist on what it means for us to be a person and not give individuals freedom to grow.

Families can do this more than any other kind of community. So family is the first place where we have to practice freedom to be an individual understanding of how we are in community and in relationship with others negotiating boundaries, saying we're sorry, when we make a mistake, accepting our own responsibility and accepting apologies from other people and not holding grudges. Recognizing that our life together as a family or as an intimate community will continue to move forward through the Spirit which animates those communities.

Being beloved community at the closest level means giving individuals space to be themselves and still being supportive of one another. It means articulating the values that we hold in common and reorienting ourselves to those values, and apologizing and accepting apologies.

In Beloved Community, we share values and a hoped-for future. We can make our families communities of grace, forgiveness and love.

Churches can also strive to be examples of Beloved Community. Both Royce and King had the church in mind as potential Beloved Communities.

Royce believed Beloved Community was animated by the Holy Spirit. King experienced that kind of spirit in the Black church which formed him and the civil rights movement. Part of the Beloved Community is that disagreements do not become occasions to ostracize anyone. King said, “The aftermath of nonviolence is reconciliation and the creation of a beloved community.” Both of these men believed that there was something special about church, they would say, as Christians, a church animated by the Holy Spirit, which invites people to stay in relationship to accept, to have those rituals of we say where we've done things wrong when we come back together again as a community.

To help make this a reality in our church, we should not be too quick to judge one another. Be clear about your own values, but make room for other people’s opinions. Help remember the history of our church and help shape its future. Be open to the presence of the Spirit in our midst. And we must be respectful of the different cultures that make up our church and not assume that we are all the same.

Now, this can be the sticking point of Beloved Community in a church. We can focus so much on the good things that we don't realize when we need to reconsider our story or make amends. Shared history, shared future loyalty to the same goals, openness to the possibility of staying in community through hard times: That's Beloved Community. I walk through First Unitarian Church and I see where our history has taken us on what our history has been is not necessarily what our future is going to be in terms of our church identity. But nonetheless, we can remain loyal to the same goals and values that we've had all the way along.

You know, our history over 235 years has been pretty white, European in its heritage, Protestant in its form, and there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s good to know where we come from who we have been. Our future, though, must be different. Like the future of Worcester, our future is multiracial, multiethnic, diverse in class, education and experience. And we're going to be challenged to be open to that future, which is different from the past that we've had, but nonetheless is animated by values of the inherent worth and dignity of every person, of freedom of worship, of encountering the Spirit through the community. In Beloved Community, we are loyal to those ideas and together, we walk into the future.

Beyond church, the big question is how to build a Beloved Community in our society as a whole. How do we get to a community of all humans that can share values, that can understand its past, work towards a shared future, and accept reconciliation?

Ever since Dr. King was preaching and teaching, America has wrestled with his words. He expressed his own frustration with middle-class White communities who thought he was too radical. Some Black activists thought he wasn’t radical enough. And at the moment that he connected America’s racism to its hunger for war, he was killed for what he proclaimed.

And still today racism, poverty and war—the evils against which Dr. King fought—cost people their lives and their dignity. We mourn today as our nation seems to move closer to war. We mourn over devastating fires that threaten the lives of humans and animals. We mourn the climate change that fuels the flames. Income inequality, racial inequality, war—the challenges Dr. King fought are still ours today.

Beloved Community may sometimes seem like a dreamy vision. But the best advice I’ve come across lately about how to achieve it as a society is down-to-earth and practical. Work together to elect officials who will enact anti-racist policies. Implement policies which support human dignity in our workplaces, our communities, our states and our nation. Make changes locally and vote nationally. Don’t worry if we can’t educate people out of prejudice; just work to change policy. Protest war, support antiracists, build community across lines of difference. Continue Dr. King’s work toward Beloved Community.

Let me conclude with loyalty. Loyalty is at the heart of Beloved Community: loyalty to an ideal and a shared, dreamed-of future. Ruth practiced loyalty to Naomi, loyalty beyond birth, ethnicity, nation or creed. She took the history and ideals of Naomi’s Jewish people. Naomi practiced loyalty to Ruth, bringing her into her family, loving her, expanding her understanding of “my people” to include a foreigner. They were loyal to something bigger than bloodlines. They were loyal to their ideals of love and commitment. We can be like Ruth and Naomi, practicing Beloved Community in our families, our church and our world.

Series Information

Martin Luther King, Jr. had a dream that America could live in the Beloved Community of racial reconciliation. Mahatma Gandhi had a dream that India could be free. Both of them believed in nonviolence. We have work to do to carry on their efforts and live into their dreams for humanity.